As any developer with a minimum amount of experience delivering software, I had to manage software projects. From having a long and boring Functional Architecture Document to not having a ticket in JIRA at all. Either way, it was my responsibility to deliver it on time.

When I started managing projects, I started as everyone else: micromanaging. If I have control of everything that happens I will be able to estimate the work to be done, I will be able to split it, and I will be able to finish by the deadline. Spoiler: no.

However, I never managed to do it correctly. I'm not a micromanager, I don't know how to do that because I am too lazy to follow every movement from someone. So I had to find other ways to do my job.

Investigating, as many others, I found about Agile Software Development, about Scrum,

Kanban, Scrumban, SAFe and tons of blog posts. However, I've found several issues

with the content I've found:

- They focus on the practicality of the day to day: ceremonies, how to layout cards...

- Their focus on the tradeoffs is shallow.

- They completely ignore about how to measure either failure or success.

Also, due to how our industry works, it's really template oriented. People prefer to work with a template, something already designed, and don't think about it. Scrum requires 2-week sprints? Then, we do 2-week sprints.

However, software delivery is extremely hard due to two main reasons:

- Software is complicated.

- Developers are complicated.

Take into consideration the example of estimating a chunk of work. Let's say that you are building a new web page, and you want to add a new button. This button is nothing fancy, so you estimate it as 2 days of work. Or maybe is it 3 story points? Do we estimate using fibonacci or T-Shirt sizes? Whatever, your team mate will estimate something different.

Usually, after you realise that half of the team estimates in 2 days of work, and the other half of the team in 5 days of work, you let the team discuss. In these conversations, the team mostly talk about vibes, there is not much to back any of the estimations. Usually these discussions end with any of the two estimations, depending on the team they will go to the safest bet, being the pessimistic estimation, or the most optimistic estimation, or halfway.

And how many of your estimations have been accurate? My estimations are not really accurate, to be fair.

And after some thinking, and tinkering with my ideas, I decided to change how I do my software delivery management. Because at some point you realise that consistency is more important than speed. It doesn't matter if you deliver the button in 1 day, if you are going to deliver the next button in 2 weeks. You can't plan your products with that amount of uncertainty.

So I stopped foreseeing, and started forecasting

It kind of started with a concept that I've learned at Thoughtworks when I was leading teams there. We started adopting lean inception (from Paulo Caroli) which is a process to bootstrap a project: brainstorming, scoping and prioritising work at the team level.

However, there is one specific exercise that made impact on me: the Technical, User Experience and Business Review. Despite it's long name, the process is relatively simple. However, from the exercise, there is one important part that made me change how I would estimate forever. Uncertainty ranking.

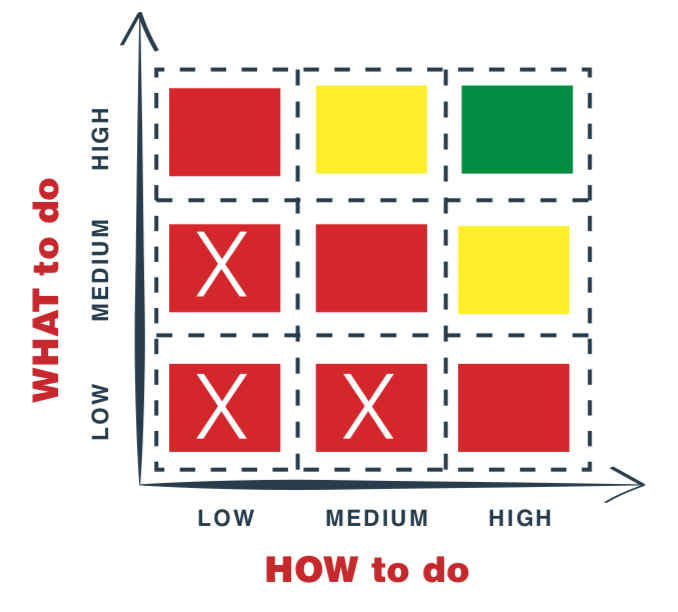

Uncertainty Ranking, from Lean Inception, by Paulo Caroli.

Uncertainty Ranking, from Lean Inception, by Paulo Caroli.

Essentially, you answer two questions, and their answers will assign a colour to a task:

- Red: High Uncertainty

- Yellow: Medium Uncertainty

- Green: Low Uncertainty

There is also the option of high uncertainty with a cross, but that's more from the lean inception process to discard tasks that are not yet suitable for an MVP: not relevant for now.

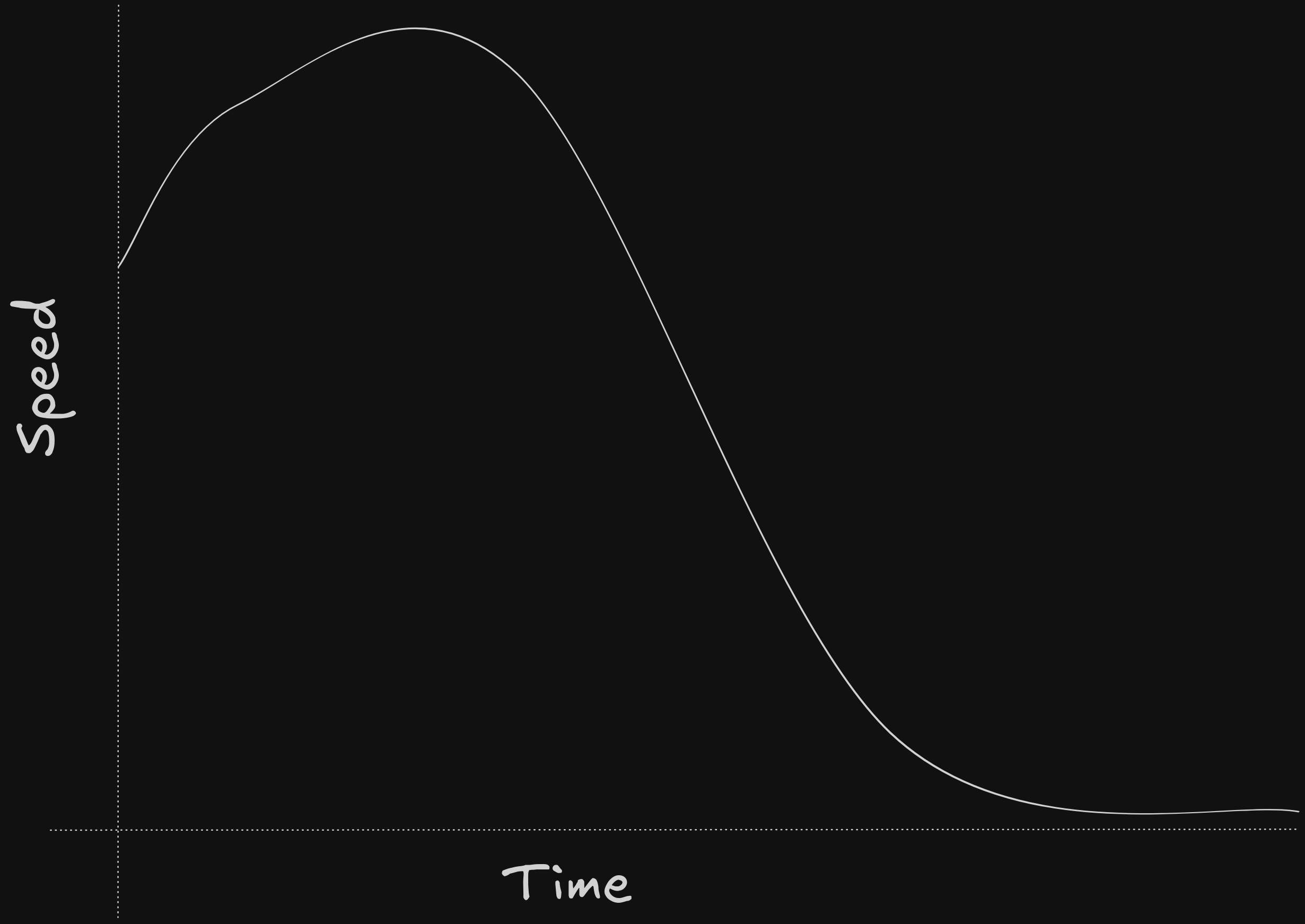

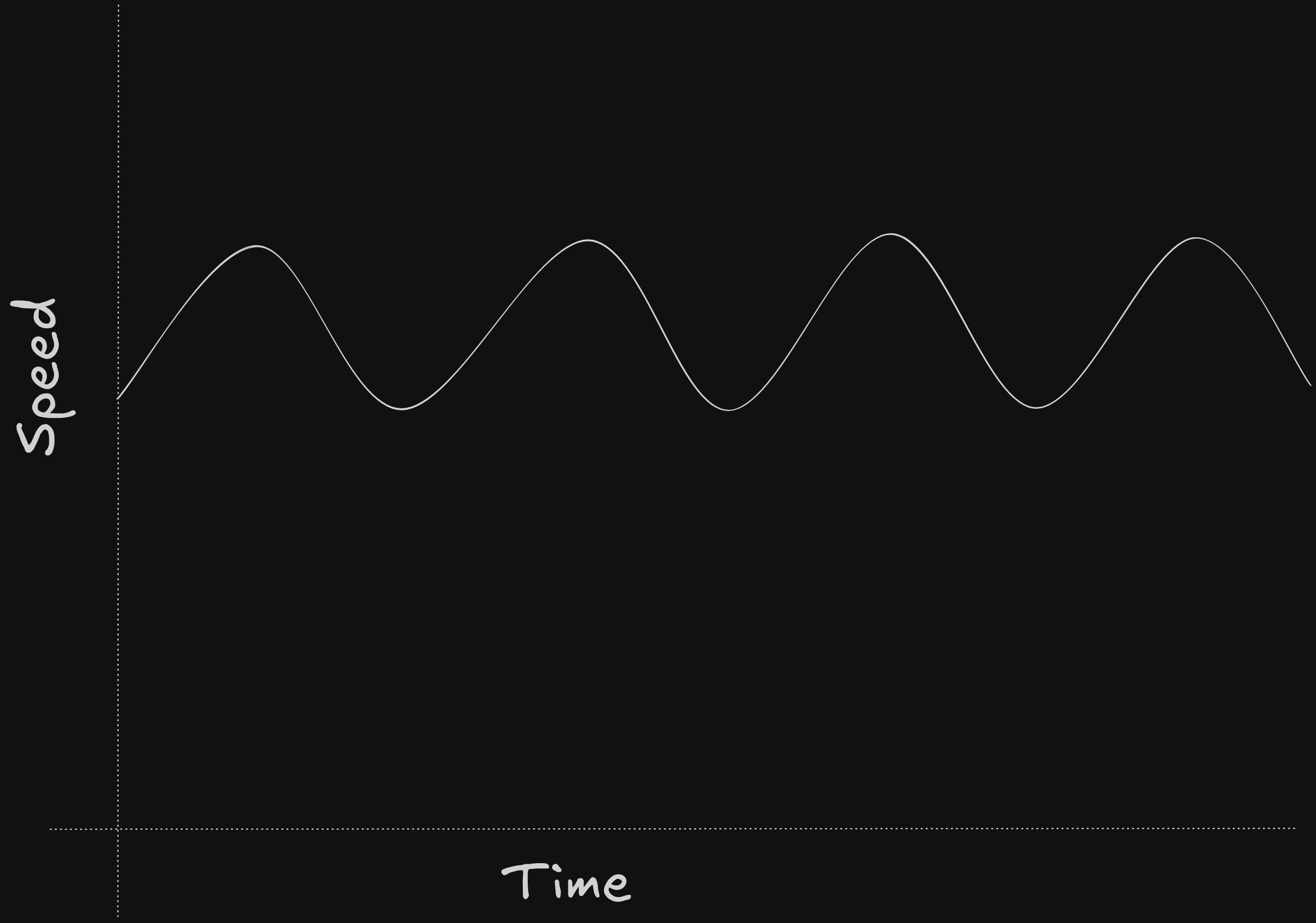

Later in the process, to prioritise work, there are some relatively simple rules that are used to know how to group tasks together. This process aims to keep consistent delivery, not raw speed. If you put all green cards together at the beginning of the project, you'll fake your speed, make decisions that might be affected later by more complex, uncertain tasks later in the project, when you work on red tasks.

However, if we mix red, yellow and green tasks together, we'll be tackling complexity and uncertainty at a semi-constant pace. Overall, the raw speed of the delivery will be slower at the beginning, but it will be consistent independently on how long is a project.

Also, by clearing out uncertainty and unknowns, important architectural decisions and assumptions are validated earlier, limiting the risk of having to redesign the solution or part of it. This, essentially, reduces the amount of work to be done by just doing the hard work consistently earlier.

This consistent pace allows us to forecast

However, we don't need to calculate speed. Speed is irrelevant, as it's extremely inaccurate. If you can make a task in 2 hours, 2 days or you can implement 3 story points in a week is just a vanity metric. Each task is different, our understanding of it is different and uncertainty makes estimates inaccurate by definition. While you can measure if a green task is a day of work, the complexity arises when you work on a red task that might change your perception of other tasks.

So, what I'm doing right now is to use statistics. What is the chance the team finishes by a specific date? However, my team was already doing estimates with numbers, so how can I be more consistent without changing the practices the team is already comfortable with?

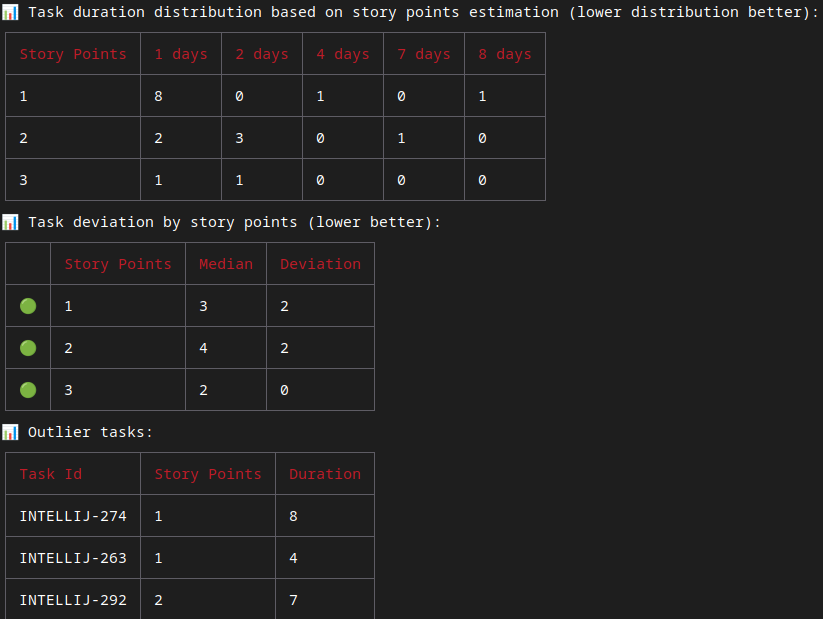

First, I decided to map estimations to uncertainty, basically:

- 1 or 2 story points: Green

- 3 or 5 story points: Yellow

- 8 or more story points: Red

Then, I made a simple script in JavaScript that consumes the JIRA API to calculate the amount of time and deviation for each of the tasks. That's how I mapped uncertainty to the actual margin of error.

Later, the same script uses a Monte Carlo Simulation to forecast when we are going to finish a specific scope.

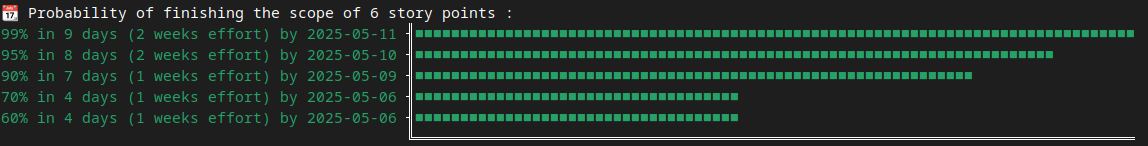

The script basically runs a Monte Carlo Simulation, based on the historical data, to forecast when the team is going to finish. By using Monte Carlo, there are some questions that can be statistically answered that are relevant when planning a new project:

- How much time does it take to deliver the project?: Take the 99% percentile.

- What are the chances to deliver on time?: Look at the summary.

- How reliable is the estimation? The closer are the delivery dates, the better.

- What are the chances that, a task with high uncertainty, will delay us?: Look at the deviation of other high uncertainty tasks.

- Is it worth to parallelise?: The script has a --parallel flag.

And the best thing, this is cheap

The team just "estimates" story points, but now they are not estimating time, they are estimating uncertainty: that's the natural meaning of story points. Building the script and some additional tools on our JIRA took a few days of work (you know, burn downs, team stats and so on) and the script takes a second to run, so I can keep track of the delivery date weekly easily.

The fun fact

In my mother tongue (Catalan) we have the word "Estimar", which is pretty close to "estimate". However, the meaning is pretty different. In Catalan, "Estimar" is "To love someone".